eLearning Self-paced

Understanding Hemostasis for Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) and Radiation Proctitis (RP)

Overview

Guide to Study

eLearning Activity

Understanding Hemostasis for Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) and Radiation Proctitis (RP)

The purpose of this module is to create awareness of the bleeding disorders GAVE and Radiation Proctitis, discuss why they occur and explore the treatment options available to patients. We will review the basic definition of each disorder, followed by an in depth discussion of the clinical implications and therapeutic options available for patients.

GAVE: Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia

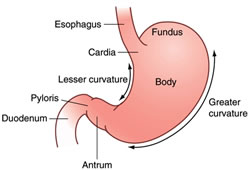

Exactly what is GAVE? The technical name for this condition is gastric (stomach) antral (the end part of the stomach) vascular (blood vessel) ectasia (dilated blood vessels), otherwise known as GAVE and first described in the literature by Rider et al. in 1953. These dilated blood vessels may leak or rupture, causing intestinal bleeding.

As the name implies, the disease generally manifests itself in the distal portion of the stomach, the antrum. The typical appearance of GAVE consists of visible columns of red, dilated vessels which course along the longitudinal folds of the antrum. This appearance has been likened to the stripes on a watermelon rind, hence the term “watermelon stomach”, another name for the condition, coined by Jabbari et al. in 1984.

Although GAVE is considered a rare medical condition, it accounts for up to 4% of all non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeds. Typical initial presentations range from occult bleeding causing transfusion-dependent chronic iron-deficiency anemia to severe acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding. Most patients with GAVE suffer from chronic medical conditions which are thought to be causally related to it. Cirrhosis of the liver is found in 30% of GAVE patients. Data obtained from screening gastroscopies on patients undergoing liver transplantation suggest that 1 in 40 patients with end stage liver disease has GAVE.

Overall, GAVE is found more frequently in females. The majority of non-cirrhotic GAVE patients are females (71%), with a mean age of 73 years, whereas cirrhotic GAVE patients tend to be younger (mean age 65 years) and male (75%).

In non-cirrhotic patients with GAVE, autoimmune diseases are most common, with incidences of 62% for autoimmune connective tissue disorders, 31% for Raynaud's phenomenon and 20% for sclerodactyly. Other conditions described in GAVE patients include scleroderma, chronic renal failure, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, valvular heart disease, familial Mediterranean fever and acute myeloid leukemia.

Symptoms of GAVE

Patients often seek medical attention based on their symptoms, such as chronic fatigue, melena (black tarry stools), vomiting of blood (bright red or with the appearance of coffee grounds). The diagnosis is then based on the clinical history, endoscopic appearance, histological changes of gastric tissue samples as described by a pathologist, and blood work. GAVE is characterized by dilated blood vessels within the stomach's mucosa and submucosa. The abnormal tissue can bleed profusely, which results in the patient’s experiencing iron deficiency, requiring repeated transfusions.

The cause of GAVE remains incompletely described or just not known. There are many theories, but the most common is that GAVE is often associated with certain disease states. Up to 30% of patients with GAVE have liver cirrhosis. The other 70% of GAVE patients have a high incidence of various autoimmune disorders including scleroderma. Stomach symptoms in scleroderma are due to slow emptying of the food into the small intestine. The retention of food in the stomach leads to a sensation of nausea, vomiting, fullness, or bloating (also known as gastroparesis).

In some people with scleroderma, the stomach can also have telangiectasia (dilated blood vessels) lining the walls of the stomach. This is also known as "watermelon stomach" due to its appearance on endoscopy. Slow and intermittent or rapid bleeding from these dilated blood vessels can cause anemia (low red blood cell count). The person may or may not have stomach symptoms and may only feel VERY tired and fatigued.

Although it is a rare disorder, Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) causes up to 4% of non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Ultimately, treatment of the underlying medical co-morbidities may lead to resolution of GAVE.

| Etiology (causes) | Unknown, but has associations |

| Associations | Autoimmune disorders (like Scleroderma) Chronic liver disease |

| Clinical Presentation |

Fatigue, melena and/or acute bleeding |

| Endoscopy | Watermelon stomach |

| Complications | Anemia ± transfusion dependency |

Ablation therapies are typically first line treatments in GAVE. However, gastroenterologists may try different options, depending on the patient and the progression of the disease.

Lifestyle Changes and Nutrition

Before any invasive treatments, patients should first try lifestyle and nutrition changes. They should avoid NSAIDS and alcohol and take iron supplement to address the anemia. These changes can decrease the need for transfusions, however, lifestyle changes lack a long term solution for chronic patients and the patient most often will ultimately need a transfusion.

Pharmaceutical

Evidence for pharmacological therapy with Tranexamic Acid and steroids is limited, stemming from case reports only. These have been used if endoscopic measures have failed to stop chronic blood loss. The oral medication Tranexamic Acid stops the bleeding through an antifibrinolytic mechanism, but is fraught with limitations and complications. Steroids are used to control the symptoms of scleroderma, however some of the side effects of steroid usage include gynecomastia, menorrhagia, steroid-induced diabetes mellitus and Cushing-like illness.

Endoscopic Band Ligation

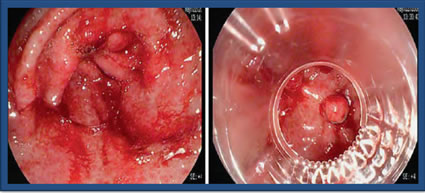

Endoscopic Band Ligation (EBL) is performed endoscopically by placing small rubber bands around the bleeding areas. This is typically used for esophageal variceal bleeding and sometimes used in the setting of non-variceal bleeding, such as GAVE. EBL requires fewer sessions when compared to Argon Plasma Coagulation (APC) and can be a salvage after APC failure, however, it can lead to complications, such as epigastric pain, ulcers and perforation. Currently, there is limited data on the success of EBL. This picture represents GAVE before and while undergoing ligation with 5 bands.

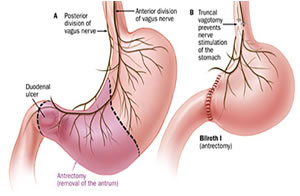

Surgical Antrectomy

Antrectomy is the surgical resection or removal of the gastric antrum. It is an invasive procedure associated with significant complications, such as ulcers, diarrhea, dumping syndrome and malnutrition. The surgical antrectomy should be reserved for unresponsive cases as it is associated with a high mortality rate of 5%-10%.. Antrectomy is usually reserved for patients with recurrent bleeding or other conditions such as malignancy, perforation, or obstruction.

Endoscopic

The initial management of GAVE patients often includes an endoscopic intervention, which typically has been argon plasma coagulation (APC); however, despite repeat APC, some patients require frequent transfusions.

Even though these therapies are relatively inexpensive, they often need to be repeated over the course of several visits to achieve hemostasis. Other therapies include Nd:YAG (neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet) laser coagulation, which has fallen out of favor due to the higher risk of perforation given the deeper thermal effect.

Endoscopic sclerotherapy, the use of a heater probe, and cryo-therapy (freezing) for treatment of GAVE have also been described in the literature. These are similar in the same therapeutic response as APC. Complications can include epigastric pain, ulcers and perforations (up to 24%).

Endoscopic RFA

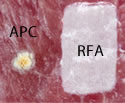

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) provides a controlled depth of ablation that limits the coagulative effect to a depth of 0.5-1mm. Blood vessels associated with bleeding for GAVE are thought to be confined to the mucosal layer within this targeted depth of ablation. The RFA electrodes come in a few sizes. The physician determines the size of the electrode based on the extent of the affected area. The electrode surface area and high-power density allows for rapid treatment of a broad area of affected tissue (< 1 second per application). This represents the largest treatment area of any thermo-coagulative device indicated for GAVE. Notice the picture comparing APC to focal ablation.

Using RFA, with this larger electrode, hemostasis is achieved through the delivery of RF energy combined with a tamponade (the stoppage of the blood flow to an organ or a part of the body by pressure) effect from the mechanical pressure of the bipolar electrode.

In a recent webinar, Dr. Scott Corbett stated that, based on his own experience and opinion, he only "does one session to achieve hemostasis, compared to 3 times with APC. Even though APC is less expensive, the cost of the procedures goes up when you add in the multiple times a patient comes in for the procedure (anesthesia, staff, etc.)."

There are promising results with over 65 peer-reviewed publications describing the safety and efficacy of ablation with the RFA System in the GI tract; although the studies on GAVE are not as voluminous, they are forthcoming with more adoption of the use of RFA for GAVE. Dr. Goss and Wallace conducted a 6 patient GAVE case series and reported fewer required treatment sessions (1.7) to increase hemoglobin levels (from 8.6 to 10.2 g/dl) and reduce transfusion dependency at 2-month mean follow-up. Four of six patients had previously failed treatment with APC.

McGorisk et al reported an open-label prospective cohort study of patients with GAVE refractory to APC. Twenty-one patients were enrolled in the study, and underwent endoscopic RFA to the gastric antrum using the HALO-90 ultra ablation catheter until transfusion independence was achieved or a maximum of four sessions were performed. Six months after completion of RFA therapy, 18 of the 21 patients (86%) were transfusion-independent. The mean hemoglobin increased from 7.8 to 10.2 g/dL, and there were two adverse events reported (minor acute bleeding and superficial ulceration), both of which resolved without intervention.

It is widely believed that GAVE is under-recognized and that it is often misdiagnosed as antral gastritis. Tsai et al. reported an average latency of five years before antral vascular ectasias are identified as the origin of GI blood loss. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind the possibility of GAVE in the differential diagnosis of chronic occult upper GI bleeding in a patient with iron deficiency anemia that is resistant to conventional treatment.

Radiation therapy (RT) is one of the most common treatments for cancer, with nearly two-thirds of all cancer patients receiving radiation at some point during their treatment. Radiation uses high-energy particles or waves, such as x-rays, gamma rays, electron beams, or protons, to destroy or damage cancer cells. While it can be very effective at destroying cancer cells, it can lead to complications, such as Radiation Proctitis (RP).

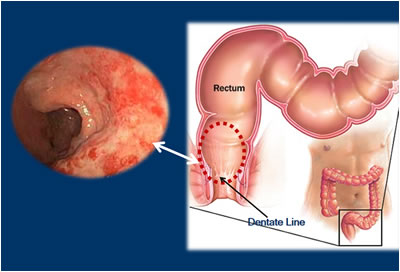

Proctitis is an inflammation of the lining of the rectum. The rectum is a muscular tube connected to the end of the colon. The stool passes through the rectum on its way out of the body. Radiation therapy can cause chronic radiation injury that may lead to long term complications, one of which is bleeding. The rectum is involved in 90% of these patients; it is thought that the rectum's proximity to the pelvic organs undergoing treatment and its relative immobility predispose it to chronic radiation injury.

RT can cause both early (acute) and late (chronic) side effects. Acute side effects by definition occur up to 3 months after RT and are usually self-limiting. Chronic side effects occur 3–6 months after RT or even years later. Approximately 5-10% of patients receiving radiation therapy to the pelvis will develop radiation "proctopathy.” The probability of developing the injury is related to the volume of rectum irradiated, total RT dose, RT technique, and dose per fraction. Also, individual patient factors can influence the susceptibility to Chronic Radiation Proctitis (CRP): comorbidity of vascular disease, diabetes, connective tissue disease or inflammatory bowel disease, specific conditions such as smoking, and concomitant chemotherapy. The median age is about 73, with males comprising about 72% of cases. Hematochezia (passing of bright red blood in the stool) is the primary presenting symptom, and most patients (57%) are transfusion dependent. The term "proctitis" is somewhat misleading since it inaccurately implies a chronic inflammatory condition. As a result, some authorities refer to this condition as a chronic radiation "proctopathy.” However, because radiation proctitis is still used commonly, it will be used in this topic review.

Radiation proctitis involves the lower intestine, primarily the sigmoid colon and the rectum. Note the diagram and the dotted circle marking the commonly involved anatomy.

Acute side effects, by definition, occur up to 3 months after RT and are usually self-limiting. Acute side effects include diarrhea, mucus discharge, urgency, tenesmus, and uncommonly bleeding.

Chronic radiation proctitis has a delayed onset. The first symptoms often occur 3 to 6 months following radiation exposure but can occur at any time, with up to 30 years post-irradiation being reported. Patients may seek medical attention for one or any combination of the following symptoms:

- Bloody stools

- Diarrhea

- Urgency

- Tenesmus (painful urgent unsuccessful attempts to defecate, even when bowels are empty)

- Rectal pain

- Anal incontinence

With more chronic RP, patients may be subjected to repeated transfusions and it is often difficult to treat medically.

CRP should be suspected in any patient who has had pelvic RT and presents with the symptoms mentioned above, even if the radiotherapy took place years ago. Diagnosis by endoscopy is important to exclude other causes of proctitis (infectious colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diversion colitis, ischemic colitis, diverticular colitis) and a second malignancy.

After the patient presents with the sign and symptoms, endoscopy of the rectum typically shows dilated and friable mucosal blood vessels proximal to the dentate line.

| Etiology (causes) | Chronic radiation injury |

| Associations | Occurs in 5-10% of patients following pelvic radiation |

| Clinical Presentation | Bloody stools, diarrhea, tenesmus, urgency, rectal pain and anal incontinence |

| Endoscopy | Inflamed mucosa, dilated and friable mucosal blood vessels; ulcer, fistula and stricture formation may be seen |

| Complications | Anemia ± transfusion-dependency |

Lifestyle Changes and Nutrition

Ablation therapies are typically first line treatments for RP. However, physicians may offer lifestyle and nutrition changes and a management strategy before trying the endoscopic ablation or surgery. Patients should avoid NSAIDS and alcohol and take iron supplement to address anemia. Medical treatment with a low-residue diet and steroidal or non-steroidal enemas has been disappointing, with patients often still requiring transfusion.

Pharmaceutical

Evidence for pharmacological therapy with formaldehyde, steroids and aminosalicylates is limited and stems primarily from a few case reports. The results have been limited, with high bleeding recurrence rates and subsequent suboptimal durability. Formaldehyde will stop the bleeding, but it is fraught with limitations and complications, such as anal-fissure formation and bowel necrosis requiring resection.

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT)

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) was recently reported to be effective for the treatment of chronic radiation proctitis. It has been reported that some patients received as many as 30 HBOT treatments and a few have gotten up to 60. Treatments consist of 60 minute sessions 5 days per week; the number of sessions varies according to the clinical response. Although efficacy rates are up to 89%, adverse effects are related to the high atmospheric pressure and hyperoxia, and may include middle ear and sinus barotrauma, pulmonary and central nervous system oxygen toxicity and chest tightness. Other complications include claustrophobia, visual change and euphoria. HBOT is time consuming and expensive and there are limited facilities that can offer this type of therapy.

Surgical Option: Proctectomy

Proctectomy is an inpatient procedure involving the surgical excision or removal, of the rectum. Patients with recalcitrant bleeding from the rectal mucosa may undergo proctectomy. This is a morbid procedure in the irradiated pelvis and can be associated with significant blood loss. Surgery for irradiation bowel injury is technically challenging because of adhesions and poor tissue healing. It should be reserved for unresponsive cases as they are associated with significant morbidity/mortality.

Endoscopic

As with GAVE, additional treatment options include argon plasma coagulation (APC), heater probe, Nd-YAG laser, cryotherapy and RFA. These therapies often need to be repeated several times to achieve hemostasis. The initial management of these patients often comprises one of these endoscopic interventions, with APC frequently used. APC is considered the preferred therapy, with an overall success rate as high as 80%. However, it has been associated with serious complications (e.g., perforation, fistulas, and strictures), and the efficacy is limited in patients with active bleeding, extensive disease and distally located lesions (anorectal junction). Other therapies include Nd: YAG (neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet) laser coagulation which has fallen out of favor due to the higher risk of perforation given the deeper thermal effect.

RFA employs a controlled depth of ablation, which makes it well suited for treatment of Radiation Proctitis as well. As a result of this controlled ablation depth, the coagulative effect is limited to approximately 0.5mm-1mm. Blood vessels associated with bleeding in RP are thought to be confined to the mucosal layer within this targeted depth of ablation.

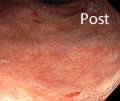

The RFA electrodes come in a few sizes. The physician determines the size of the electrode based on how extensive the affected area is. The electrode’s surface area and high-power density allows for rapid treatment of a broad area of the affected tissue with <1 second per application. RFA has the largest treatment area of any thermo-coagulative device indicated for RP. Hemostasis is achieved through the delivery of RF energy combined with a tamponade effect from the mechanical pressure of the bipolar electrode. RFA can usually be effective with only one or two treatments, however, there is a possibility of ulcerations or strictures. According to Rustagi et al.(2015), who published the largest series of patients managed by RFA (n = 39), this technique showed 96% improvement of the endoscopic severity score, 100% efficacy in stopping bleeding, and 92% of blood transfusion discontinuation, with no major complications. The pictures below illustrate the before and after effects of RFA.

Summary

In summary, radiation proctitis is a complication that commonly occurs after radiation exposure to the pelvic organs. Recognition of this condition is important, as symptoms can be quite bothersome and will often require treatment. Medical and endoscopic therapies have shown promise in alleviating the severity of symptoms associated with radiation injury.

Patients who present with the GI bleeding disorders Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia and Radiation Proctitis are frequently anemic and transfusion-dependent. These patients may be seen by gastroenterologists for coagulation therapy that will eliminate the bleeding vessels. In this eLearning activity, we have reviewed the two bleeding disorders and discussed the therapeutic approaches to obtain hemostasis for these patients.

CNE Certificate Process

Note: Your computer should be connected to a printer before completing the Post-Testing in order to permit printing your course certificate.