eLearning Self-paced

Understanding Obscure GI Bleeding

Overview

Guide to Study

eLearning Activity

Understanding Obscure GI Bleeding

Obscure GI bleeding (OGIB) has been defined as overt or occult bleeding of unknown origin that persists or recurs after an initial negative bidirectional endoscopic evaluation including ileocolonoscopy and EGD. Overt OGIB refers to visible bleeding (i.e. melena or hematochezia), whereas occult OGIB refers to cases of fecal occult blood positivity and/or unexplained iron deficiency anemia. Recent advances in small-bowel imaging, including video capsule endoscopy (VCE), angiography, and device assisted enteroscopy (DAE), have made it possible to identify a small-bowel bleeding source and therefore manage the majority of patients who present with OGIB. As a result, a recent clinical guideline recommends a shift from the term obscure GI bleeding to small-bowel bleeding. The term OGIB would be reserved for patients in whom the sources of bleeding cannot be identified anywhere in the GI tract after completion of comprehensive evaluation of the entire GI tract, including the small bowel (ASGE, 2017). Approximately 300,000 hospitalizations that occur each year are due to OGIB and many of those may be attributed to readmissions as well.

Types of OGIB

There are two classifications for obscure GI bleeding: overt and occult. Overt bleeding is the term used when blood is visible. Types of overt bleeding include melena (black, tarry stools), hematemesis (vomiting of blood) and hematochezia (passage of fresh blood in or with stool). Overt bleeding patients are generally those admitted to the hospital for evaluation of active bleeding. If a patient presents with an upper GI bleed with hematemesis, an urgent EGD should be performed. If the patient presents with lower GI bleeding, symptoms of hematochezia or melena, a colonoscopy should be performed.

The term “occult small bowel bleeding” can be reserved for patients presenting with iron deficiency anemia (IDA), with or without guaiac-positive stools, who are found to have a small bowel source of bleeding. Of all the sources of GI bleeding, only a small percentage (5%) is attributed to small-bowel sources. In occult bleeding, blood is NOT visible. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding usually is discovered when fecal occult blood test results are positive, or iron deficiency anemia is detected. The initial work-up for occult bleeding typically involves colonoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy, or both. In patients without symptoms indicating an upper gastrointestinal tract source, or in patients older than 50 years, colonoscopy usually is performed first.

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA) is often associated with OGIB. If a patient presents with IDA, it is important to identify what is causing the anemia. Other factors that may lead to IDA include serum iron blood loss. IDA can occur with Crohn’s disease, small bowel tumors, ulcerative disease, cancers and long‐term use of aspirin, ibuprofen or arthritis medicines.

Although symptoms of IDA can be mild, patients may experience a change in mood, a sense of weakness or fatigue, headaches or problems concentrating. For patients who present with IDA, physicians generally will manage the deficiency with an iron therapy medication. The physician will continue to monitor the patient to observe how they are responding. If a patient is not responding to therapy, finding the cause of the anemia can help provide better long-term patient outcomes.

Patients with blood loss and iron deficiency anemia who have a negative workup on standard examinations require comprehensive evaluation. Once findings on upper and lower endoscopy prove negative, the small bowel may be assumed to be the source of blood loss.

|

|

|

|

Melena |

Hematemesis |

Hematochezia |

The three major causes of intestinal bleeding are:

- Ulceration: a sore that develops on the lining of the esophagus, stomach or small intestine caused when stomach acid damages the lining of the digestive tract. Common causes of ulcers include bacteria H. Pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory pain relievers (NSAIDS), aspirin and Crohn’s disease. Upper abdominal pain is a common symptom of ulcers.

- Lesions (such as Angioectasias and Neoplasms): Angioectasias of the small bowel account for 20% to 30% of small-bowel bleeding and are more commonly seen in older patients. These lesions are painless. Patients often present with heme-positive stools or modest amounts of bright red blood from the rectum. Bleeding is often intermittent, sometimes with long periods between episodes. Patients with upper GI lesions may present with melena. Major bleeding is unusual.

- Tumors: Small-bowel tumors (i.e. GI stromal tumors, carcinoid tumors, lymphomas and adenocarcinomas) can present with small-bowel bleeding in both younger and older patients. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are tumors that form in the digestive tract — most often the stomach or upper part of the small intestine. GISTs begin in nerve cells that signal the digestive organs to contract, causing food to move through the digestive tract so that it can be digested and processed. GISTs can form anywhere in the digestive tract, including the esophagus, stomach, pancreas, small intestine, appendix, colon, rectum. GISTs can be cancerous (malignant) or noncancerous (benign).

There are many other causes of gastrointestinal bleeding, which are classified into upper or lower, depending on their location in the GI tract.

|

|

|

|

Ulceration |

Lesion |

Tumor |

Upper GI Bleeding

- Peptic ulcers: open sores that develop on the inside lining of the stomach and the upper portion of the small intestine. The most common symptom is stomach pain. Peptic ulcers include gastric ulcers (occur on the inside of the stomach) and duodenal ulcers (occur on the inside of the upper portion of the small intestine). Common causes of peptic ulcers are infection with bacterium Helicobacter pylori and long-term use of aspirin and NSAIDS.

- Gastritis: an inflammation, irritation or erosion of the lining of the stomach. It can be classified as acute or chronic, depending on the speed of onset. Common causes are irritation due to excessive alcohol use, chronic vomiting, stress or the use of certain medications, such as aspirin or NSAIDS.

- Esophageal varices: abnormal, enlarged esophageal veins that occur most often in people with advanced liver disease. They develop when normal blood flow to the liver is blocked by a clot or scar tissue in the liver. To go around the blockages, blood flows into smaller blood vessels that are not designed to carry large volumes of blood. The vessels can leak blood or even rupture, causing life-threatening bleeding.

- Inflammation of the GI lining from ingested materials

- Certain GI cancers

Lower GI Bleeding

- Diverticulitis: caused by small, bulging pouches (diverticula) that can form in the lining of the digestive system. Diverticula are often found in the lower part of the large intestine. When one or more of the pouches become inflamed or infected, symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, fever, nausea and a marked change in bowel habits.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): involves chronic inflammation of all parts of the digestive tract. IBD primarily includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Both involve severe diarrhea, pain, fatigue and weight loss. IBD can be debilitating and can lead to life-threatening complications.

- Infectious diarrhea: diarrhea due to an infectious etiology, often accompanied by symptoms of nausea, vomiting or abdominal cramps. It can be categorized as acute (less than 14 days) or persistent (greater than 14 days).

- Angiodysplasia/Angioectasia: vascular malformation of the GI tract. Vessel walls are thin with little or no smooth muscle, and the vessels are distended and thin. It is a degenerative lesion of previously healthy blood vessels found most commonly in the cecum and proximal ascending colon. It is the most common vascular abnormality in the GI tract and after diverticulosis, it is the second leading cause of lower GI bleeding in patients older than 60 years.

- Polyps: growths that form on the lining of the colon. Possible symptoms are rectal bleeding, change in stool color, change in bowel habits, pain, nausea, vomiting and iron deficiency anemia.

- Hemorrhoids: engorged veins in the lowest part of the rectum and anus. Sometimes the walls of these blood vessels stretch so thin that the veins bulge and get irritated, especially during a bowel movement. They are caused by a build-up of pressure in the lower rectum that can affect blood flow and make the veins swell.

- Anal fissures: tears in the lining of the lower rectum (anal canal) that cause pain during a bowel movement. Anal fissures can be caused by injury or trauma to the anal canal.

- Gastrointestinal cancers

The goals of the physician treating the OGIB patient include stabilization, followed by locating and identifying the cause of the bleeding. Frequently, bleeding will stop and start, making it difficult to locate by any diagnostic means. Therefore, it is critical to find the source early in the evaluation process.

In a study by Nennstiel et al., video capsule examinations between 1 July 2001 and 31 July 2011 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding were identified, and those with small bowel angioectasia were compared with patients without a definite bleeding source.

A total of 717 video capsule examinations were performed, 512 patients with obscure GI bleeding were identified. Positive findings were reported in 350 patients (68.4%) and angioectasias were documented in 153 of these patients (43.7%). These angioectasias were mostly located in the proximal small intestine (n = 86, 56.6%). Patients’ age >65 years were identified as significant independent predictors of small bowel angioectasia . In conclusion, the most common finding in VCE in patients with obscure GI bleeding is angioectasias. They are mainly located in the upper third of the small bowel and preferentially show a multiple occurrence. Patients’ age >65 years and an overt bleeding type can predict the presence of angioectasias in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Thus, these patients might possibly benefit from early endoscopic small bowel intervention with the possibility of argon plasma coagulation (APC) by push enteroscopy or antegrade balloon enteroscopy without prior VCE. However, in all other cases, VCE can be recommended as the first‐choice procedure, combining a high diagnostic yield with minimal invasiveness.

Discussion points with a patient can include (but are not limited to):

- Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is not a disease, but a symptom of a disorder in the digestive tract.

- Although the blood often appears in stool or vomit, it is not always visible. It may cause the stool to look black or tarry.

- The level of bleeding can range from mild to severe and life-threatening.

- Bleeding in the stomach or colon can usually be easily identified but finding the cause of bleeding that occurs in the small intestine can be difficult.

- Sophisticated imaging technology can usually locate the problem and minimally invasive procedures often can fix it.

Diagnostic Tools Used for OGIB

There are many diagnostic tools which can facilitate the physician’s diagnosis. These are outlined in the following table, along with “pro and con” considerations for each.

|

Method |

Pros |

Cons |

| CTA (computed tomography angiography) |

|

|

| CTE (computed tomography enterography) |

|

|

| SBFT (small bowel follow through/enteroclysis) |

|

|

| Tagged red blood cell scan |

|

|

| Meckel’s Scan |

|

|

| Push enteroscopy |

|

|

| Video Capsule Endoscopy |

|

|

| Crohn’s Video Capsule Endoscopy |

|

|

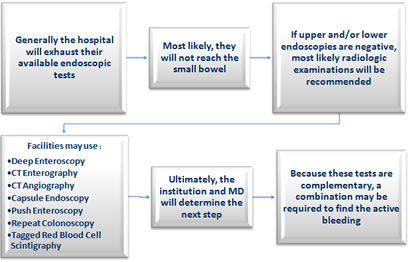

Suggested Flow for Diagnosing OGIB

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) all suggest following a protocol to manage patients. Generally, the hospital will first exhaust their available endoscopic tests, which most likely will not reach the small bowel. If upper and/or lower endoscopies are negative, radiologic examinations will likely be recommended.

Next, facilities may use deep enteroscopy, CT enterography, CT angiography, capsule endoscopy, push enteroscopy, repeat colonoscopy and tagged red blood cell scintigraphy to find the source of bleeding. Ultimately, the institution and physician will determine the next step. Because these tests are complementary, a combination may be required to find the active bleeding.

Video Capsule Endoscopy

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is considered the most frequent indication for further endoscopic visualization of the small intestine via VCE. There are 4 different Video Capsules used for locating a source of bleeding in the GI tract. It is important to recognize the technical differences, targeted anatomy, and intended uses of each capsule. Video Capsules are intended for use only in the targeted anatomy listed below. Capsule images may be limited in segments of the GI tract that are not targeted by a given capsule and may affect study interpretation.

Four available Video Capsules include:

- PillCam™ UGI: The PillCam™ UGI capsule endoscopy system is intended for visualization of the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach,duodenum). It may be used for visualization of blood in the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, duodenum) in patients who are hemodynamically stable and at least 18 years of age.

- PillCam™ SB 3: The PillCam™ Capsule Endoscopy System with the PillCam™ SB 3 capsule is intended for visualization of the small bowel mucosa. The PillCam™ Capsule Endoscopy System with the PillCam™ SB 3 capsule may be used in the visualization and monitoring of lesions that may indicate Crohn's disease not detected by upper and lower endoscopy. The PillCam™ SB 3 capsule may be used in the visualization and monitoring of lesions that may be a source of obscure bleeding (either overt or occult) not detected by upper and lower endoscopy. The PillCam™ SB 3 capsule may be used in the visualization and monitoring of lesions that may be potential causes of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) not detected by upper and lower endoscopy. The Suspected Blood Indicator (SBI) feature is intended to mark frames of the video suspected of containing blood or red areas. The PillCam™ SB 3 capsules may be used as a tool in the detection of abnormalities of the small bowel and is intended for use in adults and children from two years of age.

- PillCam™ COLON 2: The PillCam™ COLON 2 capsule endoscopy system is intended to provide visualization of the colon. It may be used for detection of colon polyps in patients after an incomplete optical colonoscopy with adequate preparation, and a complete evaluation of the colon was not technically possible. In addition, it is intended for detection of colon polyps in patients with evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding of lower Gl origin. This applies only to patients with major risks for colonoscopy or moderate sedation, but who could tolerate colonoscopy and moderate sedation in the event a clinically significant colon abnormality was identified on capsule endoscopy.

- The PillCam™ Crohn’s capsule is intended for visualization of the small bowel and colonic mucosa. It may be used in the visualization and monitoring of lesions in the small bowel that may indicate Crohn’s disease not detected by upper and lower endoscopy, and for the visualization of inflammation of the colon in patients with colonoscopy-diagnosed Crohn’s disease. It may be used in the visualization and monitoring in the small bowel of lesions that may be a source of obscure bleeding (either overt or occult) or that may be potential causes of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) not detected by initial upper and lower endoscopy. The PillCam™ Crohn’s capsule may be used as a tool in the detection of abnormalities of the small bowel. It is intended for use in adults.

The following flowchart will illustrate the decision process.

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) have guidelines for diagnosing Obscure GI Bleeding.

ACG

The most recent American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines includes an exhaustive list of recommendations for managing OGIB. But the first one that stands out is the recommendation that Video Capsule Endoscopy be implemented as first-line evaluation of the small bowel over radiology examinations. This paper suggests that patients be considered to have “small bowel bleeding” after a negative upper and lower endoscopy, and only be considered to have obscure GI bleeding following a full small bowel examination.

Excerpts from the Guidelines state:

- Video Capsule Endoscopy (VCE) should be considered as a first line procedure for small bowel investigation, after a negative upper and lower endoscopy.

- Video Capsule Endoscopy should be performed before double balloon enteroscopy to increase diagnostic yield if there is no contraindication.

- In patients with occult hemorrhage or stable patients with active overt bleeding a capsule endoscopy procedure should be performed prior to CT (computed tomography)

- Barium studies should not be performed in the evaluation of small bowel bleeding

- CTE (computed tomographic enterography) should be performed in patients with suspected small bowel bleeding and a previously negative capsule endoscopy (strong recommendation)

- CT is preferred over magnetic resonance (MR) imaging for the evaluation of suspected small bowel bleeding

- CTE should be performed in patients with suspected obstruction prior to capsule endoscopy or in patients with known IBD

- The ACG 2015 Guideline proposed the term “small bowel bleeding” as a replacement for the previous classification of obscure GI bleeding (OGIB).

AGA

The American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) position on obscure GI bleeding is that patients with occult blood loss and/or iron deficiency anemia, who have a negative workup on EGD and colonoscopy, need comprehensive evaluation, including a small bowel evaluation by capsule endoscopy, to identify an intestinal bleeding lesion. When all findings on EGD and colonoscopy are negative, the small bowel may be assumed to be the source of blood loss.

ASGE

The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopists’ (2017) position on obscure GI bleeding states that in patients with OGIB, Video Capsule Endoscopy should be the first diagnostic step in the evaluation of small bowel sources of occult bleeding once the upper GI tract and colon have been satisfactorily cleared of potential sources (if no contradictions exist). This is based on the institutional experience and availability. A follow-up push enteroscopy or DAE (Device Assisted Enteroscopy) is usually recommended for further management of positive results on VCE. Barium radiographic studies, such as small-bowel follow-through and enteroclysis, have low diagnostic yields and no longer have a role in the evaluation of these patients. Small bowel follow-through should be considered of limited value in the evaluation of GI bleeding.

The general approach to the treatment for patients with obscure bleeding is similar to treatment for any patient with active bleeding. That is, patients should be managed aggressively, with serial hemodynamic monitoring and careful resuscitation. Intensive care monitoring with aggressive resuscitation is important, since it may decrease mortality. Appropriate endoscopic, angiographic, medical or surgical intervention should be instituted.

For lesions found within the reach of a standard endoscope, treatment includes the appropriate therapy, such as electrocautery, argon plasma coagulation, injection therapy, mechanical hemostasis (hemoclips or bands) or a combination of these techniques.

More distal vascular lesions in the small bowel, such as angiectasias, may be approached for therapy through push enteroscopy or deep enteroscopy, depending upon location. Evidence shows that treatment has a positive impact on clinical outcome by decreasing blood loss and need for blood transfusions.

Masses or tumors likely require surgical intervention or intraoperative enteroscopy. Management of massive bleeding should be coordinated with surgery and interventional radiology.

Essentially, a lesion in any site of the gastrointestinal tract can bleed in an occult or obscure fashion. The most common manifestation of occult bleeding is a positive fecal occult blood test (FOB) or iron deficiency anemia (IDA). While gastrointestinal tract malignancy is a crucial consideration in this group of patients, bleeding is most often caused by ulcerative disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The most common cause of obscure bleeding is vascular ectasia, which is difficult to manage, unless a specific bleeding lesion can be identified. Routine endoscopy is important in these patients, particularly to search for rare lesions, or more common lesions with an unusual or atypical appearance. In patients who have a lesion that is not within reach of standard upper endoscopy or colonoscopy, VCE and deep enteroscopy can allow access to the small bowel. Thus, these techniques have an important role in the diagnostic approach to bleeding in these patients. Effective treatment of patients with occult or obscure bleeding is predicated on the identification of a specific bleeding lesion. When it comes to diagnosing obscure GI bleeding, timing matters. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the chances of successful treatment.

Getting an accurate diagnosis with capsule endoscopy within the first three days of admission dramatically increases the rate of successful therapeutic intervention. Further research is expected to shed light on the role of CE and deep enteroscopy, particularly whether these modalities improve outcomes.

CNE Certificate Process

Note: Your computer should be connected to a printer before completing the Post-Testing in order to permit printing your course certificate.